Going Going Gan

I have been to a tea master’s shop in Hong Kong where he brews a pot of Pu’er tea, pouring it into cups no larger than thimbles. We drink it down. There’s a fragrance, with a slight astringency, at first, and then layers of other flavors – tangy plum, honey, and sweet citrus – pile on, and the liquid tastes thicker than water.

The tea master looks at his watch, counts to 15, and exhales. We wait. And then it comes. Sweetness in the back of my throat and a cooling tingle on the sides of my tongue, goosebumps up and down my arm, hairs at a salute. A few of us look around as if the air conditioning has just kicked on. The guy next to me repositions his baseball cap. Everyone begins to burp.

This is not a ceremony.

Select foods are known to produce gan 甘, this sweet-tasting, air-chilled sensation that follows an initial sting of bitterness. Gan is peptic, but also poetic – the quicker the conversion from bitter to sweet, the more desirable, but there is no shortcutting the bitterness. Gan is an afterimage. It’s the “every action has an equal and opposite reaction” flip side, sonic boom, sugary echo or funny tingling which proves that after a period of suffering comes joy. And burping. In Chinese, gan is often paired with the word hui 回, which means “returning.” Yes, gan is acid reflux that’s good for you.

Not surprisingly, all gan-producing foods are native to China. China has long endured famines, foreign invasions, social unrest, and cruel leaders.

Translate gan from Chinese to English and you get “sweet,” but go the other way around and sweet will always register as tian 甜. Tian is sugary, tian is when someone is being sweet to you, tian is what you say when someone is being a kiss-ass.

Gan is a story. It’s motion from one place to another. The Chinese character 甘 is a picture of a tongue, with a mark pointing to the area where sweetness is tasted. It also looks like a cup, a farmer’s water bucket, a well, a manhole, a used guillotine, a pain de mie loaf pan, a ladder. It’s the Chinese character for mouth with extensions added: long arms holding a weapon. This club, this horizontal staff, this line on top, is written first in the stroke order.

I grew up in one of two Chinese American households in the town of Los Alamos, New Mexico, during the Cold War, so the packages that arrived from my grandparents in Taiwan were always a source of excitement – for the mailman. We had a long driveway, so he’d always make sure someone was home before he’d huff the package to the door. Sometimes I think he lingered, curious what was inside. This was Los Alamos, after all, where they invented the Bomb. The package had probably been X-rayed and the handwriting scanned. Communication between China and the US was closed. Hey, but this writing sure looks Chinese, and so what’s the difference between Taiwan and the communists anyway?

As a teenager, I was jonesing for a pair of Nikes, a ten-speed bike or an Atari console, so nothing that came in the triple-ply cardboard box bound by yellow nylon straps stood a chance of being remotely cool. The box smelled like mushrooms. My brother would get Little League caps and I’d get a foldable gardening hat the color of puke. This hat accompanied the seeds I could plant and raise into “lettuce” by sheer willpower in the New Mexican desert. My brother got keychains with trucks and big logos; he got figurines of the Monkey King and his royal buddies. I got jade bracelets that never fit over my hand. “You’ve got such fat hands,” my parents would say, soaping up my fingers, but giving up when my knuckles became even more fat and swollen. I got diaries. Every year, with the same blunt gold key tied with red string and taped to the back cover.

“Gan is not just a taste, it’s an often eerie sensation that something or someone has come and gone.”

For my brother and I to share were elementary-level Chinese-language books, full of cheaply illustrated tales of citizenship and morality, and my parents could never resist commenting, even though they knew it wasn’t fair and they were being stupid, how we weren’t reading Chinese at even that level, despite our being 5-7 years older than the Taiwanese first-graders these books were intended for.

I remember packages of dried squid that smelled the way my hat looked. Dried plums that sucked out all the moisture out of your mouth and glued your teeth to your lips. Dried seeds that looked like African beads. Mushrooms so purple they didn’t seem legal, jars of salty preserved turnips, bamboo shoots with chiles, preserved tofu that always leaked a sour and fermented liquid. I remember long sticks of twisted leaves resembling thin cigars, which my mom would drop into a cup of hot water and pull out 30 seconds later. She’d take a sip and offer it to my dad, then me, and when I said it was gross, my parents would say, in the same tone they took when discussing my Chinese reading skills, how in America I had acquired soft bones, how I expected everything to be sweet and candy-like, and had no concept of the idea of something bitter being good for you. Bitter represented hardship and suffering, and to endure it meant hope, fortitude, strength (yes, all those Chinese characters now inked onto biceps or printed on kitchen trivets), this semi-fluid concept that things will get better. After the bitter comes the sweet. Here in America I did not know of suffering. Mom would joke about forcing me to drink some to teach me something about culture, and then she’d finish her mug, inhaling and exhaling like a bad actor performing a smoking scene.

I didn’t get it then and I still don’t. Must we “endure” this suffering? Outside of China, bitterness doesn’t represent hardship – it is the hardship. It’s nice to think there’s a poetic way to justify suffering, but it’s also naive not to imagine some ancient Chinese empire using the idea of gan to keep the miserable masses from protesting. Throw them a little bone to chew on, stay complacent, wait for it, the sweetness is coming. Tell them it’s OK to be where they are and in the end they will be satisfied – just stay passive. That long stroke at the top of the Chinese character becomes a lid.

What’s bitter? Chicory. Walnuts. The skin of the ginkgo nut. The cherry leaf wrapped around mochi. The inner core of an apricot seed. The inner core of an umeboshi plum. Quinine. Pumpernickel bread, grapefruit pith, and yes, the cookie part of an Oreo … right?

Lettuce when it goes to seed. Lettuce in hot weather. Dandelion crowns, mizuna, mustard greens. Unsweetened chocolate.

But none of those have gan. Gan is not just a taste, it’s an often-eerie sensation that something or someone has come and gone. A little like the way “bittersweet” is used more often in describing a relationship rather than a specific taste. No food actually tastes bittersweet.

Gan is found in ginseng (a rhizome valued for its medicinal properties and resemblance to miniature humans) as well as in licorice root (not the red twisted candy), but not in star anise or anything made with anise oil, which tastes like licorice without the special bitterness. That cool sensation from the first cigarette of the day? Licorice root is used as a flavoring agent in certain tobaccos.

“The soil in Yunnan province, home of all the old Pu’er tea trees, is red from excessive amounts of iron oxide.”

The sweetness of gan combines with the taste of iodine and lavender in grass jelly, an opaque black dessert eaten during the summer and made from boiling a grass called mesona. Gan is found in bitter melon, the lumpy cucumber-looking thing with the hollow middle, more gourd than melon, often stir-fried with a salty fermented black bean. It also appears in “bitter nail” tea (kuding cha 苦丁茶) – made from the Chinese privet plant, a species of holly similar to Yerba Mate – which was what my mom was so fond of in those packages from my grandparents.

Lastly, gan is found in Pu’er tea picked from old trees. Unlike bitter melons and mugs of bitter nail tea, which are rather one-dimensional in terms of taste (sorry, Mom!), Pu’er tea has flavors ranging from dried plum, orchid, ginseng, rose, honey, wet compost, garden soil and apricot. The gan in Pu’er is a bonus, and often comes bundled with qi, weird tingling movements of energy that may cause goosebumps, flushed cheeks, and the hairs on your arm to freak out. It’s dependent on the mineral content in the leaves, making the age of the tree, soil, climate, and harvesting method significant factors of terroir, similar to the great vineyards of France.

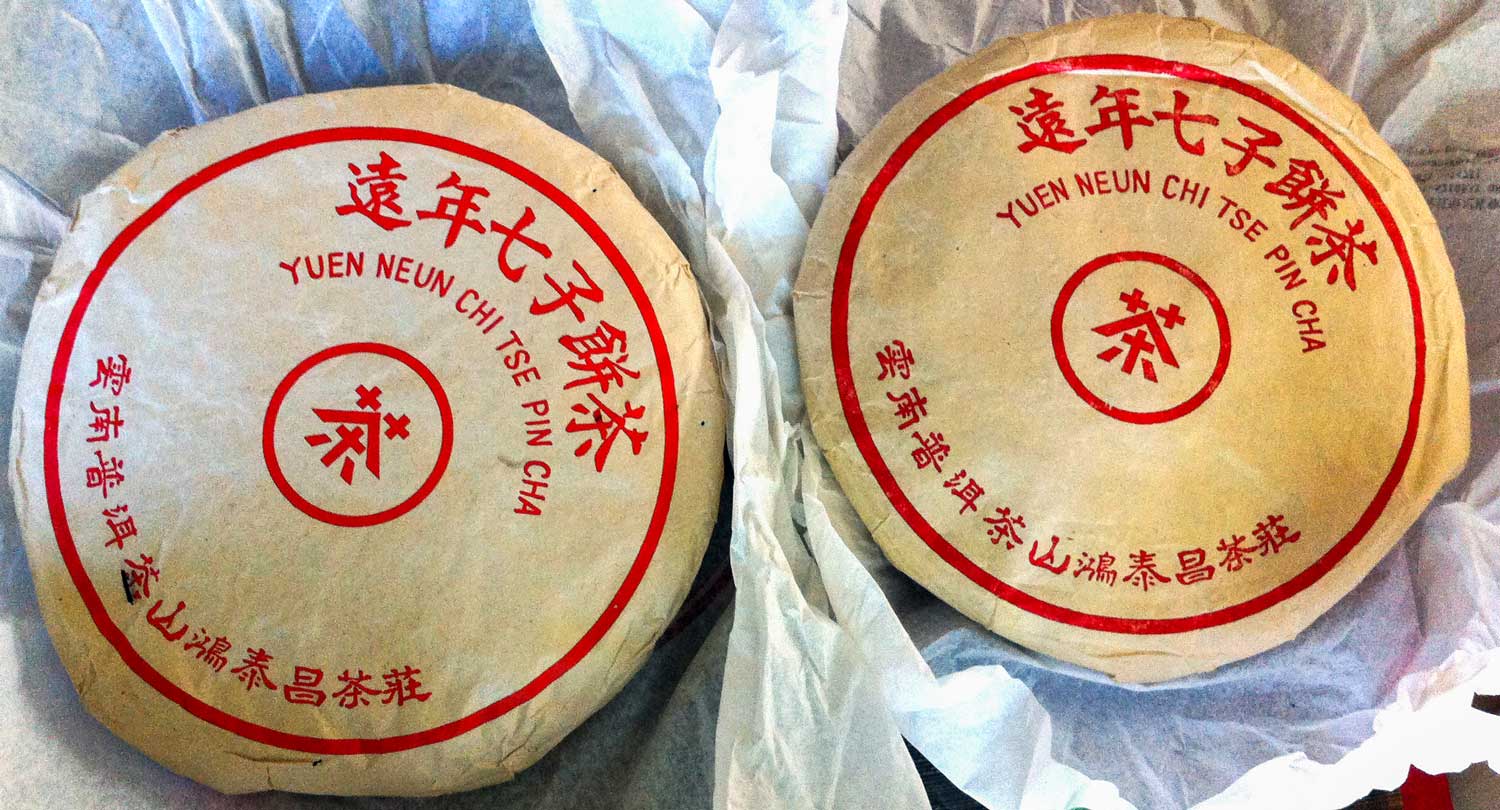

Pu’er tea is known worldwide as the dark murky tea served in dim sum houses, but certain Pu’er teas (and technically there are two kinds: raw and ripe) are collected, hoarded, valued for their age, and readily faked. A newly processed and relatively inexpensive batch of Pu’er tea might have the same amount of gan as its aged relative because gan does not develop over time. It must be there from the beginning. Rock-bottom cheap tea gets its flavors sprayed on (sort of like dog food) but there is no nozzle for gan. A tea that claims to be 50 years old made from 1,000-year old trees has a lot to prove. The traditional paper packaging is primitive and easily detached from the tea it wraps. A few leaves from old trees can be mixed with leaves from younger trees. Crappy Pu’er is just bitter. Aged crappy Pu’er is bitter Pu’er slightly mellowed.

Pu’er is often pressed into pucks or coins or commemorative shapes that can weigh several pounds. New or old, it’s the only tea that hurts when it hits you. These aged lumps of tan and brown vegetal matter can sell for several thousand dollars an ounce.

It takes 400 years for a tea tree to be considered “old.” Young trees don’t absorb enough from the soil, are picked too often, and are encouraged to produce too many leaves or grow too fast. Old tea trees grow slowly, producing very few leaves, but each leaf is packed full of minerals that have been sucked up by their large root system. Mineral content is what allows the gan to express itself. The minerals are attracted to saliva, forming tight bonds which make the tea taste thick and flavorful. The soil in Yunnan province, home of all the old Pu’er tea trees, is red from excessive amounts of iron oxide. Sometimes, when the tea tree roots intermingle with the roots of camphor trees, the sweet cooling sensation of gan takes on the sweet cooling sensation of Tiger Balm.

Lately there have been a host of scientific studies analyzing the health properties of Pu’er – its probiotic nature, its fat-busting, cancer-fighting, cell-regenerating and boob-lifting qualities. What is missing from all these findings is gan. Old tree Pu’er tastes amazing. Old tree Pu’er has gan. It must be there or else you shouldn’t be paying the money that is charged for old tree Pu’er. Which isn’t that much, when you only need five grams to brew several cups worth, and it’s cheaper to buy it young and age it yourself, instead of splurging on some really aged stuff.

The gan in some Pu’er I have drunk is so strong, so terrifying, that at some point, I have to stop drinking it. I cannot drink any more tea. This is not a question of willpower or resolve or caffeine or bladder size or lack of focus. I have to stop. Because once the gan reaches a certain level, nothing tastes better than plain water. I want to mainline it straight from the tap. It’s just water, but it will taste candied, sugary and very thick. The repeated drinking of little tiny thimbles of tea with high mineral content has built up a coating in my throat and mouth. The minerals and spit are hugging each other so tightly that water not only fails to dilute the flavors, but the action of drinking re-energizes the particles like outstretched fingers running down a sheet of scratch-n-sniff.

The taste for gan has not traveled far beyond China, but it could. Maybe if they dropped the stodgy part about bitterness and suffering and instead emphasized the temporal state between bitterness and sweetness. That pause. Unlike its friend umami, whose tongue-tingling delight ends as soon as it’s swallowed, gan isn’t a flavor. Gan is about sharing something you put in your mouth that isn’t all about flavor. Gan is curious. Gan is a transformation that may or may not happen. We may fail to find it, or have a muddling of sensation – no returning sweetness – but the act of listening transforms the moment. The more you try to figure out the speed, the less you know what it is. Gan is a gift, and it’s neither here nor there. If you’re lucky, it’s a glorious buzz, this muddy footprint, this temporarily sunning dog.

text by Angie Lee, photos by Angie Lee and Linda Louie

Recommended reading

In Tea in China: The History of China’s National Drink, John C. Evans describes the East India Company’s “diabolically ingenious” scheme to balance Great Britain’s trade deficit with China. The weapon of choice? Opium. Corporate interests developed interlocking global markets for opium and tea that “made the English and Chinese populations mutually dependent.” Tea concerns also informed Peking’s lackluster response to the drug crisis sweeping the southern frontier:

China’s Manchu rulers always cast a wary eye on South China’s tea fortunes and viewed the opium traffic as a way to reduce the riches of Canton merchants and put South China to sleep, thereby lessening the threat of revolt.

The spectacular wealth to be gained and lost in cash crops like tea and ginseng turns their histories into fables. Tales of this lucrative commerce are populated by archetypes: honest farmers, cunning forgers, desperate prospectors, fast-talking grifters, crooked lawmen, insatiable merchant kings. A screenwriter would pitch the television series as Robin-Hood-meets-Deadwood. There’s a word for that in Chinese: jianghu, which Jinghong Zhang’s Pu’er Tea: Ancient Caravans And Urban Chic defines as

a space located between utopia and reality ... a social world in which knights-errant achieve romantic dreams, but chaos and risks still remain. Cheating, poisoning, and robbery are frequent occurrences in the world of jianghu. Cheating and forgery are also prevalent in the case of Puer tea, making the quest for “authentic” Puer difficult to accomplish.

Zhang argues that jianghu gives the framework to understand the Pu’er business. Dispatches from tea country do sometimes come across as posted from an alternate dimension. A tea vendor and key source for Max Falkowitz’s Saveur feature, “The Pu-erh Brokers Of Yunnan Province,” swears him to secrecy before granting insider access. Having vividly portrayed the incredible psychedelic potency of a few sips from a private tea stash, Falkowitz surrenders to the unreality of the experience. “I know how this all sounds,” he admits. “There’s a lot of dreamy language that makes its way into tea culture, but good pu-erh really is drugs.”

Angie Lee is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles. Her work has been published in Witness, Diagram, Airshipdaily and Entropy. She sells Chinese tea and teapots at 1001plateaus.com and offers tastings with Linda Louie from Bana Tea Company at Huntington Gardens in Pasadena. Angie blogs about tea, coffee and dogs at moonquake.org. Technically she eats Chinese food every day.